Reading palms, assessing health

When Guiseppe Valacchi first demonstrated the Nu Skin Carotenoid Hand Scanner, I was intrigued. In less than a minute, without drawing blood or swabbing saliva, he had given me a carotenoid “score” that could be correlated to my personal intake of fruits and vegetables. My mind was racing. How did it work? Was it accurate? Could I use this machine as an engaging outreach tool to spark conversations about increasing fruit and vegetable consumption? Could we monitor folks? Maybe have a contest for the most improved score? Could this tool encourage behavior change and improve health status?

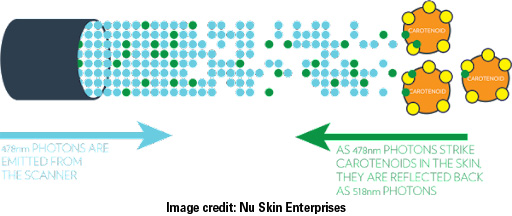

Valacchi, a researcher at the Plants for Human Health Institute (PHHI), specializes in how oxidative stress affects different body organs, particularly the skin. His lab equipment includes the carotenoid scanner which works using Raman spectroscopy. Raman spectroscopy uses a specific wavelength of light to identify distinct compounds. For example, the carotenoid hand scanner emits a 479nm wavelength beam of light directed at the palm of the hand; the light bounces off carotenoids which are present in the fat of the hand. The light waves that hit carotenoids bounce back at 518nm. The scanner measures how much 518nm light is bounced back, indicating the quantity of carotenoids encountered in the skin. Carotenoids are fat soluble compounds and are more or less distributed evenly in a person’s body fat. This makes it a convenient and non-invasive way to measure the carotenoid levels on the ulnar side of the palm.

Research has demonstrated that carotenoid levels are typically higher in someone who eats foods high in carotenoids, such as sweet potato, carrots, spinach and mangoes.1 However, there are two important caveats. Carotenoids are fat soluble, meaning these foods must be consumed with fat in order for them to be absorbed by the body.2 AND, carotenoids are often bound tightly within the food matrix, so cooking carotenoid-containing foods to break down the cell walls will allow the carotenoids–consumed with a (healthy) fat–to be optimally bioavailable. Eating raw carrots with ranch dressing, adding avocado to a salad or adding nut butter to a smoothie satisfies the fat requirement to ensure carotenoid absorption can occur. Roasting carrots, tossed in olive oil, sauteeing leafy greens or pureeing pumpkin or sweet potatoes would offer even more carotenoid “bang for your buck.”

High stress levels, sun exposure, or a diagnosis that is using up the antioxidant ability of the carotenoid (such as macular degeneration), will result in a lower score.3

One recommendation may be to identify ways to de-stress or reduce time in the sun, but in conjunction, you can offer a PhytoRx, identifying specific carotenoid-containing foods. Increasing the quantity and variety of antioxidant carotenoids can boost tolerance to damaging cellular oxidation in the body caused by environmental stressors.

Citations

- Burrows, T. L., Williams, R., Rollo, M., Wood, L., Garg, M. L., Jensen, M., & Collins, C. E. (2015). Plasma carotenoid levels as biomarkers of dietary carotenoid consumption: A systematic review of the validation studies. Journal of Nutrition & Intermediary Metabolism, 2(1-2):15-64.

- Stevens S. L. (2021). Fat-Soluble Vitamins. The Nursing Clinics of North America:56(1), 33–45.

- Darvin, M. E., Richter, H., Ahlberg, S., Haag, S. F., Meinke, M. C., Le Quintrec, D., Doucet, O., & Lademann, J. (2014). Influence of sun exposure on the cutaneous collagen/elastin fibers and carotenoids: negative effects can be reduced by application of sunscreen. Journal of Biophotonics, 7(9):735–743.

This article was part of the May 2022 e-news FRESH Rx. Subscribe for similar content delivered to your inbox monthly.

- Categories: